Since its invention, photography has focused on the human being. Yet its language, the rhetoric of the image, and the very notion of the central, exclusive place of the human being in the global picture of the world are subject to criticism nowadays. The exhibition explores photography and the images having passed from it into the new media. It reinterprets the human experience and the experience of the universality of vision, with which photography has associated its mission throughout the twentieth century.

Contemporary conversations about the human impact on the ecosystem and the political perspectives opening up to society hardly ever have positive context. The human condition, whether it be a set of specific psychophysical phase-states, political circumstance-states, or moral and symbolic capital-states in the contemporary ecological agenda, is now on the verge of exhaustion. Artists and social philosophers are increasingly turning to the theme of non-human agents, shifting the focus of human attention to the things beyond, which are potentially superior to the human. It is customary to speak of the incompleteness and simplification of a picture of the world centered on the human being and to associate utopian ideas with transcending his body and the boundaries of his experience.

Young people are a social group that is particularly acute in realizing its otherness and being individualist, and on whom anxieties and hopes for the future are traditionally projected. In her project, close to classical photo-reportage in the genre, Ksenia Tsykunova shows the sharp contrast between the private world of apartment parties and the concept of “millennials” in the public sphere. The author alternately tries on two roles: on the one hand, she works with a social, isolating view of the new generation, and on the other, she shares several poetic images of close friendship and frank communication.

Today “Human condition” seems to be a formulation of the past. In Russian, this universal concept, covering both personal experience and the global agenda, failed to catch on and has always required contextual explanations. Not without reason, this notion has been translated differently as human destiny, conditions of human existence, human conditionality, etc. At the height of its popularity, in the middle of the 20th century, it implied an active and constructive notion of the individual, a notion of values shared by the community, of the openness of the public world, and was inextricably linked to the modern humanist paradigm, in which media were accorded the status of a trustworthy mediator. In René Magritte’s The Human Condition (La condition humaine, different versions painted in 1933, 1934, 1935), the frame of a window with an idyllic landscape is eclipsed by a painting in which the landscape view continues, flowing from the outside world into the room without distortion or stitching. This notion of coherence, of harmony between the outer world and the inner human world, achieved through the unity of vision, was inherited from Surrealism to the classic documentary reportage of the mid-century. That happened primarily thanks to the large-scale exhibition “The Family of Man” (first shown at MoMA in 1955), whose main program was a reflection of the global “human condition”.

Documentary photography postured itself as a universal language, not distorted or discredited by ideology, and the contemplative mode of interaction with the world it dictated was analogous to political consciousness. An intended naivety that today has lost its persuasiveness.

Today, the relationship between the external world and the inner world of the individual is conceptualized as a drama, a deep split, a knot of contradictions. For a long time, photo-reportage has existed in the Humanist paradigm of the unity of values and the identity of the external and the internal. But now it is rapidly losing ground, photography is being valued less, and the understanding of its nature, traditionally built around the concept of “documentality”, is being blurred. Nevertheless,

in the post-truth era, the demand for the following remains acutely relevant: for forms of authentic expression, for a language that would provide a direct appeal to the human experience as opposed to the confusing rhetoric of the media, for an experience that would bring us to each other, that would show us how to be together.

Although the belief in photographic truth is increasingly viewed as an outdated habit of the observer, artists and photographers are in no rush to declare the potential of the “documentary” exhausted. What is the relevance of the language of photography today? Isn’t photography a thing of the past together with the twentieth century? What can the expressive language of realistic photography give to the modern statement? What forms does it take in the world of new media?

The author’s principal creative strategy is to overcome the legacy of humanistic photo-documentary: today conventional reportage is commonly associated with appropriation, appropriation of the experience of the Other. Petrokovich’s images are born at the intersection of aesthetic experience and ethical gesture. The strangeness embedded in them points to the limitations of the human gaze and point of view. The exhibition includes works not included in the author’s series.

The artists exhibited use photographs to convey their experience of interacting with the human, its lack or overcoming – whether it is a state of affect or a revelation of the unconscious, longing for wholeness, or a sense of belonging. Thus, Ksenia Tsykunova, Nikita Shokhov, and Ilya Rodin turning to the canon of documentary photography use the language of new media to give new acuteness to the sense of rupture between the viewer and the hero, the social construct and the contradictory personality. Arnold Veber and Sasha Chaika show human nature dissolving into a chaos of instincts and fetishistic sensuality. Tanya Chaika and Olga Vorobyova speculate on the potentiality and forms of fusion with nature. Ksenia Yablonskaya, Chapaykina and Smyrna, and Sofia Pankevich build a new language of images and metaphors for expressing extreme mental and physiological states. Alisa Gorshenina, Vera Barkalova, Ekaterina Kovalenko, and Alisa Gill reorganize the filming and creative process as folklore action, ritual, and group performance, elevating the viewer to the collective unconscious or a liminal situation. Sofia Tatarinova and Ivan Petrokovich conceptualize the fundamental conditioning of reality by the observer’s gaze as an ethical dilemma. Finally, Anastasia Mleko and Maksim Ivanov offer their original variants of the fusion of optics and psyche mediated by a non-human – technical or natural – agent.

For each of the authors, a drama unfolds when it’s impossible to have an absolute approach and knowledge of the Other through sight. Thus, photography helps highlight the values of integrity and communication and throws light on the problem of their implementation.

As media, it appears that photography has not a pleasant status of an obsolete language for discussing the issues underlying its identity. However, contemporary creative practices allow us to review documentary and humanism metaphorically. Photography still symbolizes the very “form of reality itself” that leaves its trace in our inner world but gets rid of the burden of illusory transparency of representation with which society once endowed it. As a media that gives greater visibility and a specific sensual tone to the collision of two worlds: outside and inside a person, it still retains its relevance today. No less important is the motif of active vision, also genetically linked to photography.

In her program text, “Vita activa” (in the first edition of 1958 it was called “Human condition”), Hannah Arendt emphasizes the importance of action as the basis of human community. Comparing media space to global theater, a show that hypnotizes and renders the subject passive, critics of contemporary society often oppose modern media, including photography, to real activity and dream of a radical rejection of media in general. Instead of the utopia of a world not connected by mediality, contemporary authors suggest using the cultural and discursive photography background to discover the potential for overcoming the crisis: in their works, photography overcomes its contemplation, its aloofness from the world and becomes the act that connects people and enlightens the human existence.

For Veber, the nightclub chronicle is a manifesto of life-perception and life-making. You deny the value of subordination and manners in favor of instincts and fetishes, and your body releases adrenaline and sexual energy. Thus, indoor parties symbolize the inexorability of entropy. Fragments of the body, bits of gestures, touches, textures of fabric, and reflections of light create an atmosphere in which the society gives way to spontaneity, so the individual is only one element in a chaotic and vivid kaleidoscope.

An appeal to nature is a common reaction to urban revolutions. The idea of purification and return to the bosom of nature takes a dramatic form in the works of Tanya Chaika. In a set of self-portraits, the artist records her vain attempts to blend into the wild landscape: she tries to dissolve in it, but it rejects her. Her snow-white skin, her awkward pose, and her inability to make her idealist dream of “returning to her roots” come true is a near-sacrificial gesture.

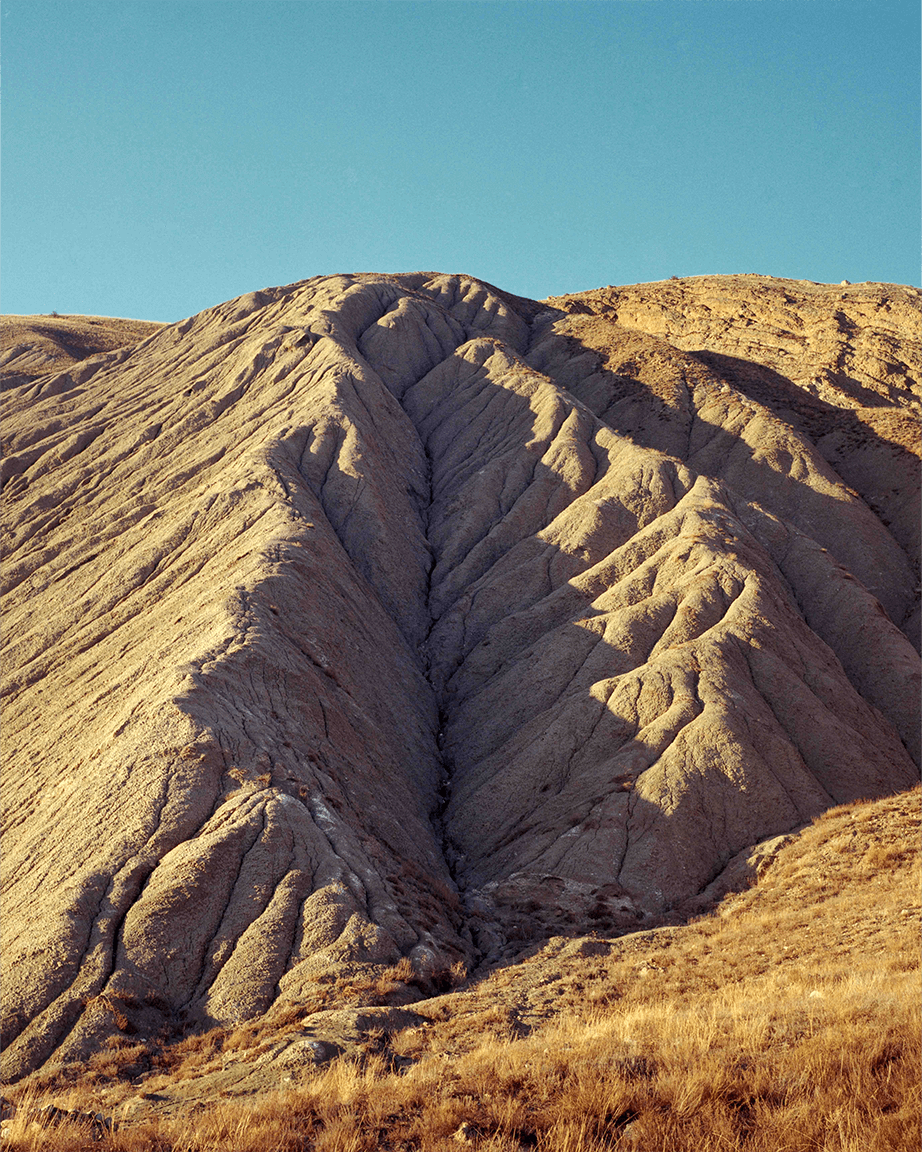

Romantic ideas about meditative contemplation, dissolution in the landscape, nature as a source of purity and spirituality, crushing power, or a key to self-discovery return to the work of contemporary artists in a new interpretation. For Olga Vorobyova the Crimean landscape becomes a central metaphor in the conversation about the image of femininity. The basis of her series is a clash of stereotypes about female roles and the idea of comparing feminine to a force of nature that is superior to human.

Drawing a parallel between the realm of the spirit and the field of DNA development, Anastasia Mleko discusses the need for eco-psychotherapy and appeals to the viewer to be more sensitive to those processes that lie outside the sphere of human sensory experience but directly predetermine it. Thus, in her photo essay, with a title as a quote from Timothy Morton, she draws attention to the biological basis of psychological mechanisms such as gaze or mimicry. Shifting her focus from the personal to the human, she addresses issues of posthumanism and the decline of the Anthropocene.

Ranged on hunting trails in Austrian forests, the wild animal figurines reproduce a natural idyl and still are well-placed in front of the attentive eye of the shooter. These crudely crafted figurines come alive as in a fairy tale, provided that the man is left outside parentheses, outside the frame. The comparison between the photographer and the hunter is widely known: having reality in his sights, the photographer seeks to capture a precious moment. The theme of absence and presence of the observer in Tatarinova’s project becomes an eloquent remark to the idea of a pure, objective view: human attention is the principal condition for the existence of this reality, undisturbed by man.

The material world, dictated by fashion, has a magical transformative power, which, impacting humans, gives birth to an extraordinary hybrid of the living and the inanimate. Sasha Chaika’s works reflect the contradictory union of body and clothing, which seem incomplete without each other, but outcry each other, opening up the possibility of a particular, fetishistic sensuality.

“Russian Alienated” is a neologism coined by Gorshenina. This original self-description grew out of an attempt to define a creative strategy based on both the search for national identity and the practice of creative individuation. For Gorshenina, working with masks is simultaneously related to the personal experience and its rejection, to the ritual dissolution in the space of collective folklore.

Alisa Gill’s work is a project of collective spiritual practice. The three-part performance, based on eschatological iconography, is intended to accumulate the maximum moral tension of the participants. Guil arranges their bodies into compositional schemes similar to a diagram or sketch in the image. This transformation of individual actors into part of an ornament serves as a metaphor for spiritual work and transfiguration.

The works from the joint project initiated by Vera Barkalova and Ekaterina Kovalenko “Ritualism” were shown for the first time in a digital space, conceived by the creators as an imitation of a dream or fantasy. According to Barkalova, free imagination giving way to scenarios, which are fixated in a person on the unconscious level, may become an effective psychotherapy tool. Digital space simulates such immersion into the subconscious. Disturbing, complex images referring to phenomena of social reality let us achieve the supra-individual, the pre-ordained in the individual consciousness.

The plasticity of the human body in Pankevich’s series reflects a complex of psychological states, complicated to be adequately characterized. “Carex” deals with mental disorders: the treatment of traumatic experiences through photography reveals the therapeutic potential of the medium. In the “Shelter” series, the artist reflects on the dual nature of striving for integrity and unity, which results in the rejection of individuality.

The series is about a Moscow student who experiences severe pain during her menstrual cycle. “Katya” is a kind of exercise in intimacy, not just a dedication to a loved one, but an attempt to get into the inaccessible bodily experience, overcoming the boundaries of the documentary genre through the artistic reconstruction of an acute psychophysical sensation.

Artists Evgenia Chapaykina and Ksenia Smyrna use the power of still life to create visual metaphors of bodily experience. The series, executed in a delicate lilac palette, is as far from human as possible at the level of images but imbued with human sensuality.

According to Yablonskaya, female fear and sexuality are related: the taboo of public discussion of body problems, the rigidity of attractiveness standards place women in a narrow emotional corridor between the desire to be desired, shame, and intimidation. In her photo essay, Yablonskaya tries to visualize the feeling of horror, of intense effect, in as abstract a form as possible, with images that refer to vivid haptic sensations.

In the title and some images, the author quotes the photo project “Arcadia” by Anastasia Tsayder. The series is based on a game, which the photographer wrote as a dedication to his girlfriend. The virtual topography of the game is based on her inner world and is essentially closed off from outsiders: there is no way to play this game. New media in the Homeland project allows us to shift the focus of attention away from the person but helps retain his invisible presence as the main background or condition of existence.

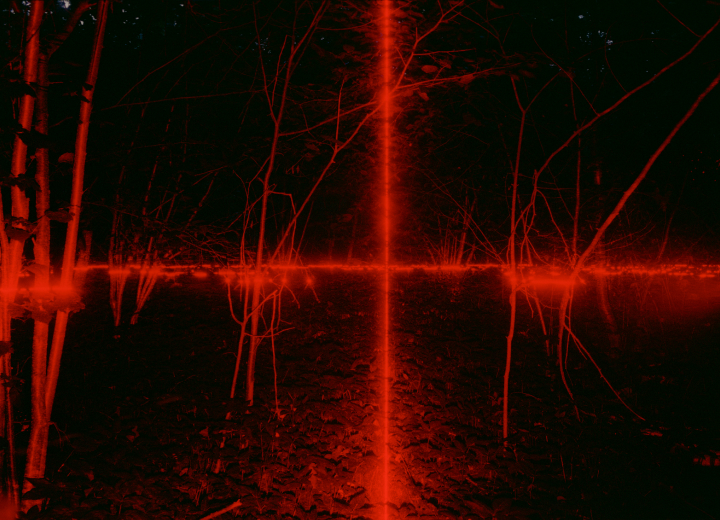

One of the technologies that preceded the formation of ocular optics and perspective, the mode of vision that gave rise to photography, was the frame for transferring an object onto the pictorial plane. In this series, Ivanov performs a kind of media archaeology, returning to a simple technical method. The artist projects the laser beam onto the vegetation and actualizes one of the fundamental problems of photography: the relation of mechanical and natural optics.

This three-part work, done in VR technology, reminiscents of avant-garde theater: a polyphony of sounds, a poetic speech, and pictorial scenes make up a story about human life. Thematically, the work focuses on the experience of racial otherness: while VR allows us to have an acute experience of an intimate sense, the text deals with the problem of the break and the work on proximity both on the social and the individual level.

Nikita Shokhov, Anna Evtyugina

Script and Poetry:

J. William Howe, Jaeda Mason, Fiona Rae Brunner

Actors:

Pearl Bedford, Heidi Dorris, Jaeda Mason, Antonette L McCaster